The who without the where becomes unimaginable.

Thompson’s Cut is where we became borderless. In October, the temperatures were high and hot so the leaves took a longer time than usual to turn on the mountains. This disappointed you because if I had come later, and if it wasn’t so humid, the trees would be bursting in rich hues of orange and red but it was beautiful to me anyway, so much so that I cried on a bench in Cedar Glades because I didn’t think anything could possibly get better than this. I was already sold on whatever this place was going to be and who we were going to be within it. We had the softness of summer and the approaching quiet of winter on our backs in equal measure, the sweet spot of autumn where nothing has quite let go but everything is preparing for it. All is trembling with life and us, cradled within. Some hope is in the landscapes, some belief that it’ll stay that way forever.

We drove north listening to songs about never leaving and you stroked the back of my neck while I read to you over the music, moving through the mountains but barely moving at all. Nothing seemed very dramatic here, just soft and gentle but this was before I had experienced summer in the south, before the strip malls and the excessive amount of plastic bags in Walmart and the punishing humidity and chigger bites made me sour and hard. Before you took me to the rodeo.

We drove out to a place where people knew each other enough to wave and waved anyway, even if they didn’t. I found this cosy and strange, so alien to my life at home in the city where even if you did know someone, you’d be forgiven for pretending not to notice them. You never know who knows your mother. So I waved at strangers passing us on the mountain, made conversation with people at gas stations, used my accent as often and as garishly as I could just so I could be welcomed again and again into the folds of this place.

That night on the mountain, you fell and cut your hands open in the dark. Your hands always made me feel calm, the symbol of vulnerability in your small, trembling palms, everything I thought I wanted to be in service to and held by. I took you back to our badly constructed tent to wipe away the blood and dig out the stones that were wedged underneath your skin. I’ll be thanking you forever…I won’t want to but I will. I took this as you cementing my role as your rescuer and my role in general. I move to the South, I tend to the wounds, you thank me for the rest of time. This is the way it would be and that sounded okay, I wanted a place here too badly to suggest anything else. Our need of being needed too strong and too fixed from the moment I first arrived to this place.

Driving out to Thompson’s Cut, we bathed in the water and let your friends go ahead while we stayed to chew on apples and cheese and talk softly to one another. A web of skin formed between us there, driven by the cooling water, the woodpeckers, an impossibly hot October sun, the leaves turning on the mountains. This place is the relic of our beginning, where we formed a fondness for quiet places. If it had been either side of autumn, if I had been from here, if you had not been seeing it through the shade of my adoring, excitable eyes, maybe things would have been different. But this was a place too easy to adore each other in. The water was a threshold, solidifying our silent and enduring commitment, a confluence of two people.

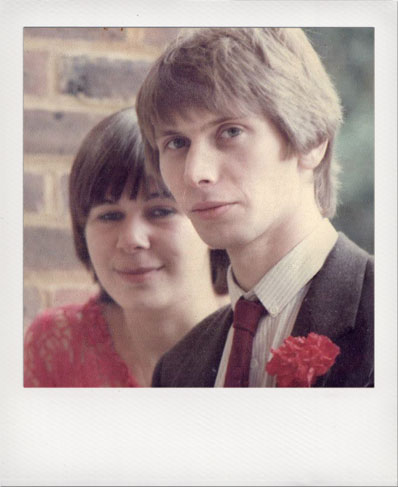

We decided as soon as we woke up the next day, we’d drive to the courthouse in Fayetteville and get married. I texted my two best friends saying my phones broken but I’m going to get it fixed tomorrow. Ps. we’re getting married as if tacking it on the end of a sentence made it less manic, more indifferent, just like a thing that made total sense. But we didn’t do it, just like we didn’t do it every other time we had the idea to get this thing fastened to forever. It seemed an absurd gesture for something already settled. So we roamed the aisles of a bookstore instead, grasping persistently for each other’s hands every time our bodies swept past one another in the narrow aisles, crouching down to read EE Cummings poems and cartoons your uncle had drawn. He had married an English woman, too. She was probably more tolerable of the anguish of quiet, angry men than I was able to be.

—————————————————————————–

New York made us tender. You flew out to meet me from North Carolina back when we couldn’t be in the same country without needing each other close. January’s brutal winds and snow made walking difficult but we walked anyway, all over the city. With a shared purpose and a shared need to be full of each other and full of what this could give us. It felt good to be in a place that neither of us belonged to. Mutual territory to project ourselves into.

We did laundry the day after you arrived and it was the most mundane thing we did together, something we needed more than anything. Sitting on yellow plastic chairs playing cards and waiting for your clothes to wash away the smell of campfires and booze and whatever other stupid stuff you had done while away from me. You always turned up smelling like campfires and I buried my face deep into your chest just to see if I could smell juniper, sagebrush, the sky in Santa Fe, all the high, wide places held in the folds of your clothes. This is where intimacy lives, not in the grand gestures or declarations of everlasting love or how much either of us would be giving up just to sustain a life but in buying toothpaste on a Thursday afternoon in the East Village, in settling your whole body into someone’s chest, close enough to feel like you’re inside and under the bones, building a home.

We talked about living in the city often and how it would swallow us both whole, too brazenly storied, no space for tenderness. We wanted infinite, quiet places that released its stories slowly over time, where a different kind of stoicism existed. One weathered by mountain winds and desert heat, everything slow slow slow, where we could grow things and grow old and unfold gently and purposefully. But those kinds of places also splay you wide open. There are no boundaries to keep you snug and sealed in. We were contained in this city, contained in the laundromat , contained under each others skin in an apartment on East 4th and 2nd, contained by the snow and the inside of Italian restaurants in the Bowery and the cinema in Brooklyn. Contained for enough time to realize just how much we needed the small, everydayness of each other.

—————————————————————————–

Rome frustrated us. It was not so much the city in all its grandeur but in the playful perfectness of it. Pasta and gelato every day. A surprise parade on the way to the Colosseum. Pizza and wine as a mid-morning snack. The Altar of the Fatherland sprung upon us as we rounded a corner. Cats among the ruins. Ancient monk bones buried in a crypt. A fancy apartment by the river and another life imagined growing fat and happy and more loving and more free and just more, more, more of everything, forever, to die here like Keats with a view of the Spanish Steps. We had already begun to fill our pockets wildly to the point of bursting with all the places that could make something of us that it all began to stop making sense. For who would we be without their soft and lively cushioning?

—————————————————————————–

Los Angeles gave us our last understanding. You came bearing the sweetest gifts from New Mexico and such eager relief to be falling into me again, made all the more sweeter by the way LA looks at night, like a soft filtered dream, like a city cast in gold. Like the startled way it’s been described a million times by a million people who have been winded by the wide streets at dusk.

We sat in a diner on Ventura and you told me you felt like you were sinking. Meaning I’m sinking under the weight of the person I can’t be for you and it’s about to fucking destroy us. I didn’t take it very seriously. You’d be fine and if you weren’t, we’d take refuge in one other, sterilize the wounds. I never thought we could fail at that and anyway, nothing bad can happen in summer, not when the days are long and hot and I was about to discover lightening bugs and how to fish and what a real storm sounds like. The entirety of it was ahead of us, rolling out like a white road under the moon. Appealing to me here, in this place where I was my most free, my most calm, was just an obsolete gesture when the future was so incredibly blinding and full.

—————————————————————————–

Arkansas made us cruel. It wasn’t all drama and violence though. Sometimes, things could get almost sweet, like stopping mid-argument to say shall we just go to Waffle House? And although you are pinned down by war, everything feels soft and wholesome, as much as it can in a Waffle House at 2am.

Many more of our storms were cut short all over the state by food, sleep, desire, friends, family dinners and a desperation to contain a whole life into small moments of panic. A raging argument about who has quantifiably experienced more grief over their lifetime intersected with a humbling discussion of where we’d raise our children. As if saying it out loud made everything okay. As long as we could talk about our kids being happy someday, then we would be fine right now. The arching of love and cruelty, the frantic push and pull of frustration at its finest and most irrational. Let’s go drive somewhere, teach me to skin a fish, I hate you, I love you, I want to marry you in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, I want to survive a natural disaster with you, I want you to leave and never come back, I want you, I want you, I want you. No matter how grown we feel, we love like children.

And it’s easy, of course, to rectify a problem when you give yourself over to the tiny, crucial things that sublimate fear and put faith back into a thing. We could fight stupendously and then drive out to the lake to catch frogs and remember why we were doing this. Nuance fixes things. Staring at each other over food for long enough to find love in there somewhere fixes things. Being able to reach across the front seat to grab your hand after I called you a terrible cunt fixes things. You can’t fix things when there isn’t a Waffle House to meet halfway at in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. You can’t drive out to a place just to feel good for a minute or reach out for a familiar body in the middle of the night. You can’t do anything. Yet even with me there, you couldn’t abandon all of our impending gaps.

And apart from the dreadful time I woke you up at 6:30am to drive me to the Farmers Market, waking up next to each other prolonged the blind faith I had in you. Every two-bit insult buried under the immediacy of warm skin and warm words. Baby, I love you, good morning, your consistent and sleepy sentiment in the most fragile of moments that cut short any desire to get straight on a plane and get the hell out of this sticky, angry place once and for all.

Most of all though, my belonging here was scrupled by your fear of letting me melt too much into it, and of your painful fact that I would never belong. Like me just existing was an attempt to force you out of orbit. But there was quite enough space for both of us and I did everything I could to scratch out my place. While you threw me against the edges of this town, I absorbed the magnolia trees and the lightening bugs and the stupid fucking snapping turtles so it would be impossible for you to wrench them from me. I absorbed your friends and your family and your grandmother’s cooking. I ate crawfish even though I hated it. I bent myself to the shape of this place and I hated you for not noticing but I wasn’t going anywhere. Not really. You must have gathered that by the amount of times I packed and unpacked my bags. You must have known I was always going to come back.

The day before I left, your aunt Mimi asked us how we met and we loved telling that story. Well we really didn’t like each other at first. And then we couldn’t live without each other. Like literally it felt like dying but we usually left out that part. Just sweet anecdotes and laughter and hey, well here we are now! Reach for my hand, gaze at me lovingly, look bashful until someone changes the subject but please no one change the subject, we need to remember. She told me she had a feeling she’d be seeing me again which I just took as more confirmation that I was in this forever, that anything could be fixed by entering a new space together, a trip somewhere, an apartment somewhere else, doing something normal and gentle in the trepidation of each others silence.

The only place this didn’t work was in the grocery store. You hated me in the grocery store. Especially if it was a WholeFoods and especially if I asked questions. It took me two years to learn to do the food shopping on my own.

—————————————————————————–

New Mexico gave us reprieve. We had done no mental preparation for a cross-country trip apart from constructing a bedframe in the back of your econoline, hauling in a mattress and a million blankets for the cold, desert nights, making a vague route from Arkansas to Colorado via places you loved, places you were desperate to show me, places I was desperate to see. I cut raggedy insulation for the windows and you wrote a ‘things to bring’ list which had my name at the very top. Must not forget Sophie. We hung little blue curtains behind the front seats and filled the van with books, clothes, lures and rods, a camping stove and a skillet. Our transient home furnished with the upmost love and one thousand tins of beans. We were going to disappear into something bigger and more ancient than we knew and it was going to fix everything. Your mum and grandmother knew this wasn’t true. I could tell by their faces that morning they fixed us with a full stomach to get through Texas. You know this could break you, right? No way. Never.

The desert called to us like a siren’s song. We were reaching for the vast, infinite places we dreamt of, where everything is quiet but there’s still a sound you can hear, somewhere, somewhere. The canto hondo ready to lull us into an abiding truce.

In Santa Fe, we got drunk on margaritas before splitting to Abiquiu for Georgia O’Keefe’s beloved mountain. Taking the low road by the Rio Grande, we passed through Espanola, rounding corners on dominating pink mesas and talking about opening a motel in a shitty little New Mexican town where all of our friends could come and live with us. We grew homes in these conversations and in little womb-like spaces which held us close together, while forgetting entirely to grow homes in each other.

Shunning the leg to Arizona, we stayed on a hill overlooking the Abiquiu Dam and the flat-topped mountain painted a thousand times, waiting for the sun to crown the hills so we could fish and play and eat green-chilli cheeseburgers at the gas station in town. I don’t know why we fought here when it was so astonishingly beautiful. Maybe because I asked you if I should buy a tomato in the grocery store and you got so mad about it we didn’t talk the whole way to Ghost Ranch. Maybe it was that. Maybe I just asked too many things. Maybe we were built so entirely on words and questions and plans that one superfluous tomato had the capability to expose our resentment to the whole of this enormous space and tear us further away from each other until we were no longer in sight. I wish I could have just run wires between our brains so we never even had to talk but just know exactly how the other was feeling and the rest could just be done through touch and sight. I feel like out of all the senses, we were the best at those two.

And I liked driving with you the most because it was the closest we had to the quiet of every day life together, just rolling smoothly and slowly along beside each other. The quotidian spaces in between the monumental excitement. Just familiarity. Just me making sandwiches in the passenger seat and you keeping things pushing forward. Perhaps boredom was the goal. Perhaps sinking into a quiet, ordinary, wordless rhythm was the goal.

—————————————————————————–

Utah made us kind. Not so much in a lasting way but in some kind of tender way at least. We drove out to places that would have taken hours and hours to hike to because you liked being where you didn’t have to share me or yourself with anything other than the wild, appeasing emptiness. I thought this was testament to how much you needed me but I think it was something else. I think it was fear. I think it was an understanding that the moment we were exposed to civilisation and opinions and skepticism, we would crumble. I was scared, all the time, but I never doubted you could keep me safe because out here, where words were few, you could.

We found some slick rock out by an old corral which promised hoodoos at its centre. Hundreds of miles from either of our homes amplified our differences except when we climbed the slick rock. The slick rock made us patient and kind and generous with our love. Differences shadowed by how much we didn’t want the other to die and how much we wanted and needed to conquer something together. Breathing in and out to each others tune was a funny, pleasing feeling. Some trepidation and care taken, some hope for the greater good. Knowing full well how to by this point, this was the one time you decided not to break me when it would have been the most effortless to do so. We were being our most industrious and our most selflessly strong. We were helping each other find footing, strategizing before making any sudden decisions, playing the long game, believing in each others own confidence to make the cut, to clear the landing.

But with the accomplishment of living, there was a dying part of us we were also facing. Because without rocks to haul each other over, without a way to dispel our own selfish needs when it mattered the most, where was our reality? What did building anything mean?

Out there in the quiet spaces, in the boundless charm of the desert, we were furthering our childish desire to become an enduring story. But driving somebody half way across the country doesn’t mean you know how to love them.

—————————————————————————–

Airports made us hopeful and desperate all at once. This is where we became untethered, slipping back into our own skin and our own countries. A shiny, nothing place marking the beginning of impatience, sweet letters and circular, longing phone calls.

Every flight was preceded by the same text. I’m boarding now, I love you meaning I am officially leaving this airspace, please don’t panic or do something dumb and hopeless. Don’t forget I’m going to come back. Don’t forget that although we are separated by 4,255 miles of gloomy blue water, I’m going to come back and I need you to make me want to.

Regardless I came back anyway and so did you, just a little changed each time, just a little more hardened by loving each other far too firmly and a little more ready to make our boundaries known, which disappeared again the moment we fell into each other at baggage claim. Utterly hopeless. But hopeful too. If reclaiming one another felt this good each time then maybe every furtive greeting at an airport gate was just another faithful chance to start from scratch, find new footing, love softer and better. A wicked belief that kept me coming back long after you ever wanted me to.

But this was still a place that bookended us, made small the endless mornings, made desperate the plans for next time. “Next time” was a good, fruitful, loving place and such a damn nice idea. We loved next time, next year, next summer, the next time I’d get to throw my arms around you at an airport gate, the next time you could drive me home to the sheltered pocket of your room which always had an adorable new configuration to optimize our comfort, to comfortably weather the storms that stirred right outside your window, storms I never got used to. Next time was never more necessary than here. Everything clung to it. When all would finally fall into line. When you wouldn’t have to return me anymore. Because that was what was so painful to you, having to give me back to a place too far to even imagine. You sinking back into your belonging and me flying away to somewhere that didn’t exist, where I was a ghost. Until one day you decided to scrap the whole brutish dance we’d become so used to and give it all up to distance. O’Keefe wrote to Steiglitz, I would hate to be completely outdone by a little thing like distance. But you don’t just give up on a thing like that. You don’t just give it all over to distance.

—————————————————————————–

The English countryside made us crazy. In a small cottage by the River Avon, you watched me sleep and felt my body retreat from yours almost every night as if it was telegraphing my unease. Not so much at being close to you but at how much the four walls of this tiny perfect place were being tampered with by having you here, how much of us they were breathing in and how much they would unload on me after you were gone. I knew all of what we made there would linger and it would never feel the same. It would feel lonelier and more absent. I would hate it. I would move out early.

But this was our God-house, enveloping us in wild devotion and pockets of consuming chaos, too small a place for two terrified people so blindly in love but everything we thought we wanted. A fecund retreat, a single warm room, older neighbours to have dinners with, good country people with good record collections and good wine, who looked at us with their knowing sympathy through the years they had on us. Disagreements turning to rage bouncing off the walls turning to quietly embracing in the kitchen turning to morning coffee and long, wet walks. We could get used to this or we could completely destroy it. Like there were only ever two options.

—————————————————————————–

Lake Ouachita helped us say goodbye. You drove me to the lake before I left so we could swim and be peaceful and it felt a lot like the first time but also a lot like nothing. Like Thompson’s Cut in reverse, a divergence of selves, a drawing apart in the cosiest way. Delicately undoing the braids is how I wanted it to end. Not in bitterness but steeped in something quieter, softer, more tender, more resigned to just being claimed by it all, by the water, each other, the muscodine wine we’d packed in a styrofoam cooler and the hammock. The hammock.

I loved it here, more than you ever knew. It wasn’t grand like the west but wild and secretive, accent dots of white and red through the trees which had began to turn ever so slightly through another punishingly hot October. I saw all my summers here. I saw us the most clearly here, regardless of my non-belonging, regardless of the time it would take to adapt to all the things I still didn’t know, time you wouldn’t give me.

The man at the kiosk told us we were lucky we came. It was the last day the lake would be open for the year. This is all you get kids, there’s nothing more after this. So we stayed on the small, empty cove for hours making our final peace. I sat on the shore sifting quartz from the rocks or wrapping myself around you in the water with a foggy bliss in my bones. Sometimes it felt like we were living in secret, like we breathed together for these brief, private doses of intimacy and the rest didn’t mean much of anything. Just dressing to what we really wanted, which was to disappear into each other, which we didn’t know how to do, which is why it never seemed real enough.

You were aware, more than me, of separation doing its delicate, slow dance but we didn’t ask questions or break the silence. All the details were slurred and fading, a mutual decision to just lean into it, lean into this thing that is pure and stormless but not quite solid enough to bear the weight of distance.

—————————————————————————–

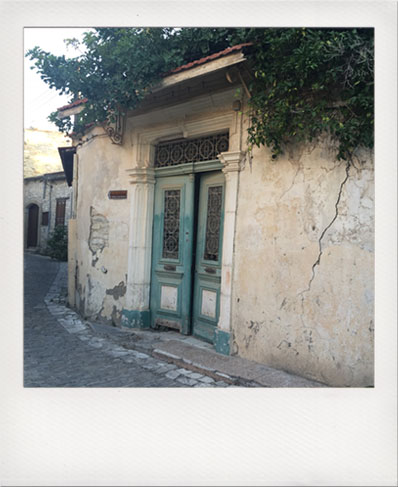

We didn’t own collective things but we had places. We built formless homes from safe and desperate distances in landscapes which could have given us the things we needed. The little lacemakers village in Cyprus with its swollen fruit trees and toothless grandparents would have taught us patience. Missoula would have taught us to endure long winters together, Oregon would have given us a garden to tend to. Your little blue house, which will never have me in it, would have given us the every day love we required, the end of day sleepiness, goodbyes which would have lasted hours at most instead of months, the me in the garden, the you cooking dinner, the us we didn’t get to know but would have most probably adored. The us we would have watched grow from a place that was ours, where we’d never have to battle over the wideness of time.

That’s where our forever lies, in all the places we’ve loved in, in the silent witnesses to our story. All it takes is a needling wind to breathe life into them for a moment. Or a lonely night. Or a song. Or the touch of other, less capable hands that don’t quite command the same spirit, by new love that strives to reach it. Perhaps they will all slowly creep into exile, become bored by everything we’ve given them or be written over by grander, more enduring stories that don’t have us in them. Perhaps it was greedy to assume they were ever really ours in the first place. Perhaps.

Such a beautiful testimony. Thank you.

This was amazing and poetic, I loved reading it. It gave me a wonderful feeling in my heart. Thank you so much <3